RICHARD SIKEN SCHEHERAZADE HOW TO

Which brings us back to Scheherazade, who had to figure out how to tell a story in a way that would never get boring, and would never end. Or the characters believe it is an imperative at least, and they feel compelled to answer the relationship's call: If you two get boring, I will die. This poem ends with the line “Tell me we’ll never get used to it.” It reminds me of a similar line, we've all said it ourselves, whether in a moment of feeling smitten or well-loved or well-fucked or even kicking back on a beach vacation, we say, “I could get used to this.”Īs a final line I think this one is paradoxically brilliant, because my other take on it is: Tell me we won’t get boring. There is a oneness present that is exceedingly tender and yet at odds with itself in that there are eruptions, tension, implosions, and violence in the poems to come. In this poem, the same light that can be seen through the windowpane possesses the bodies of the narrator and his lover. It leaves the individuals behind, it devours them, it transcends them and it is all encompassing.

The relationship, I’m guessing, is very much an entity unto itself in these poems. (Is there such a thing as knowing too much?)Īll of this imagery is set within rhetorical questions of “how.” “How it was late.” and “How we rolled.” and “How all this and love too, will ruin us.” The final lines of the poem freely go into abstractions about a relationship that seems destined to live on the edge. This is a love that breaks the law and is perpetually on the lam, and somehow, in the midst of all of this, there are kisses that produce the fruit of knowledge.

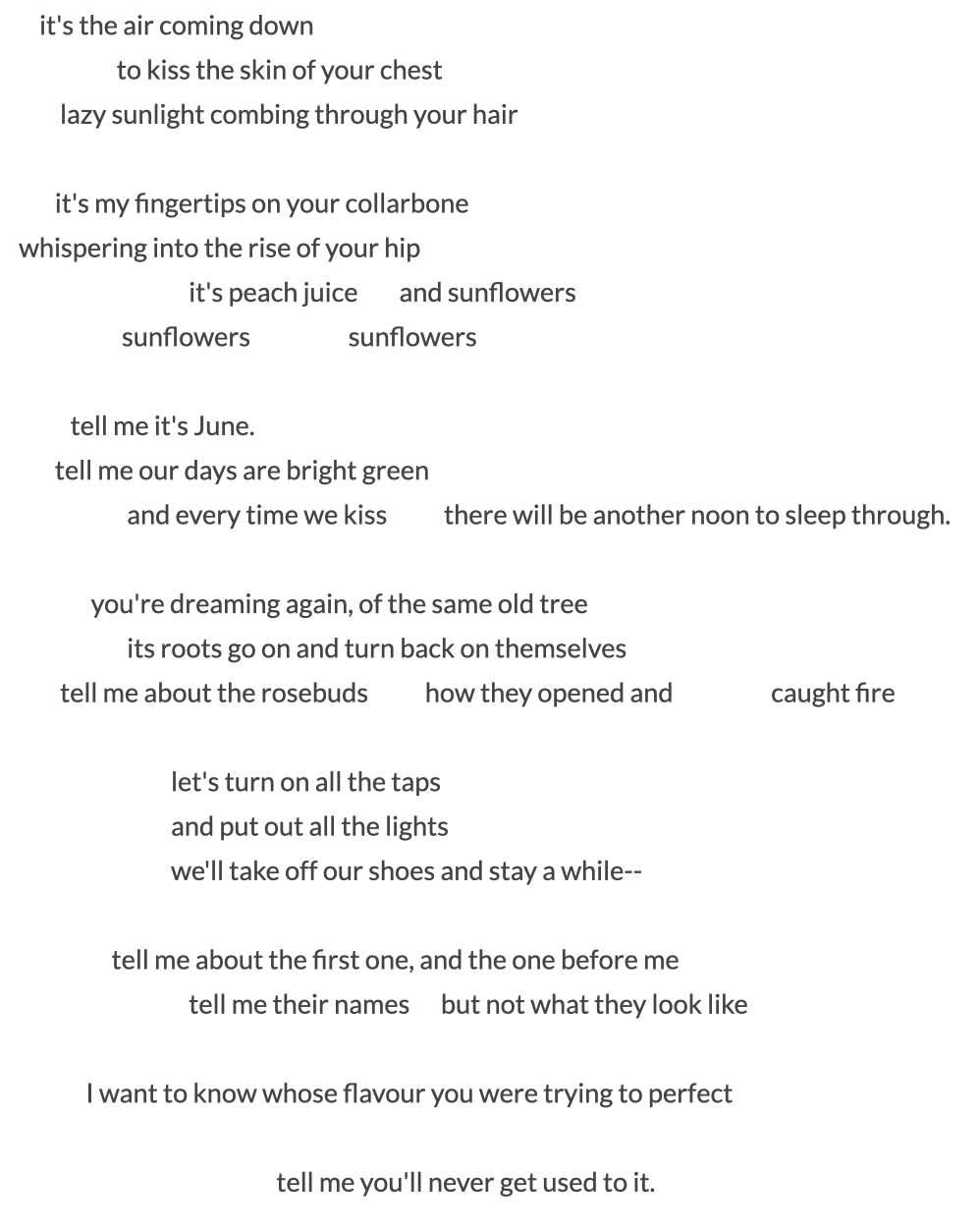

In this relationship there is an omnipresence of bullets and broken glass and blood, blood inside and outside of bodies, bodies dancing and bodies being rolled. These poems are about the kind of love that almost drowns you, time and again, but still you cozy up in the habitual aftershock of surviving each near-death experience together the kind of love that requires animals be pushed to their limit to illustrate freedom, sexual dynamic (if not the sex itself), and endurance it struggles with denial and anxiety while its origins and outcomes continue to extend outward, above ground and under. There are bodies in a lake, warm clothes for them, horses who run so hard they forget they are horses, trees with roots that do not need to end, days that are bright red, a carpet rolled up for dancing, a police radio that plays music, and a supply of apples, one more appearing with every kiss. The dream/story is the perfect set up for a collage of strong and distinct images, some realistic, others not so much. This request comes across with the tone of a child asking to be told a favorite story. It starts with the narrator asking to be told, again, about a past dream. There is just so much packed in to this short piece. We’ll see if I still feel that way once I get all the way through, as I’ve only read about half of the poems so far, but at a pretty quick pace. Selected as the poem to open this collection, my spidey sense tells me that Scheherazade is foreshadowing.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)